Housing Support Systems

HOPWA

The Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA) program was founded to administer housing assistance and related supportive services for low-income individuals living with HIV/AIDS and their families. This program is managed by HUD's Office of HIV/AIDS Housing and is known as the payer of last resort. Funding allocation is based on formula awards and competitive awards. Formula awards account for 90% of total awards and competitive awards account for 10% of total awards. Typically services and programs available to clients include some variation of:

- Housing Case Management

- Permanent housing – long-term housing support with no time limit for residence or housing assistance.

- Transitional housing – support that facilitates the movement of homeless individuals and families to permanent housing within a reasonable amount of time (usually up to 24 months).

- Emergency/Short-term housing - provides an immediate place to stay or bed to sleep if you become homeless or otherwise experience a housing crisis and have no place to go. This support can typically last no more than two weeks.

Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program

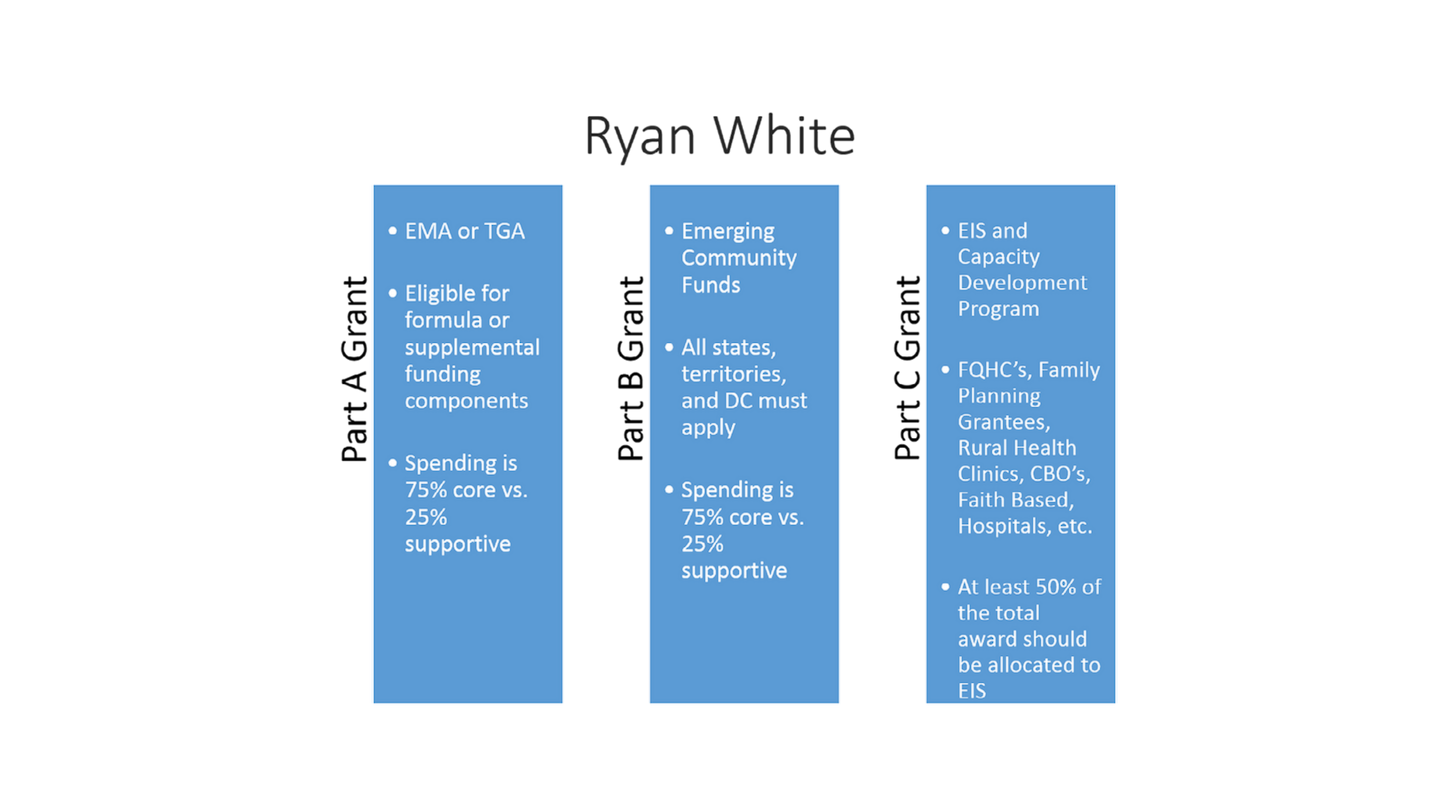

Established in 1991, the Ryan White program is the largest federally funded program for PLWHA in the U.S. It is administered by Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and HIV/AIDS Bureau (HAB). Known as the payer of last resort, funding is dispersed between 6 different parts (A-F), with Part A, B, C, and D contributing to housing services.

- Part B is the largest funded part & includes the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP)

EMA - Emerging Metropolitan Areas; TGA - Transitional Grant Areas; EIS - Early Intervention Services; FQHC - Federally Qualified Health Centers; CBO - Community Based Organizations

Ryan White Housing Support

Housing is categorized under supportive services and receives a percentage (as determined by the varying procedures for each Part) of the allowable supportive service spending. Housing-supported services are primarily intended to be temporary and transitional. Allowable services include:

- Housing Case Management

- Housing Assessment

- Emergency or Transitional Housing (up to 24 months over the lifetime)

- Housing Search and Placement

- Advocacy

For additional information and clarification, the HIV/AIDS Bureau (HAB) Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) released the Policy Clarification Notice 16-02: Eligible Individuals and Allowable Uses of Funds Housing Services Frequently Asked Questions

Housing Interventions & Resources

Permanent Supportive Housing

As the barriers impacting homelessness are better understood, housing interventions are growing to include more permanent solutions. Many programs have looked to transitional housing assistance, which provides temporary assistance. This can be a valuable safety net service for some, but there are many who need long term assistance in order to reach housing stability. In recognition of this need, Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) was developed. PSH is an evidence-based housing intervention assisting homeless individuals with accessing permanent housing and wraparound services.

Two popular PSH interventions are:

- The Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program

- Housing First Model

Rapid Re-Housing

A HUD-funded program, informed by the Housing First Model, is available to metropolitan Cities and urban Counties and States. It was established to reduce the amount of time a person/family is homeless and address the immediate needs required to obtain permanent housing.

Funds can be used for: short-or medium-term rental assistance, housing identification and relocation, and stabilization/management services.

Housing First Model

A homeless assistance program that prioritizes the most vulnerable populations to receive immediate permanent housing residence and voluntary supportive services. Residence is provided by a community organization within a housing facility.

Residents do not need to be housing ready, sober, or agree to seek treatment/care as the model relies on client self-sufficiency and readiness development. Residents sign leases and have tenant protections to avoid unlawful or manipulative action from the "landlord." There is no time limit for the residents to stay; many voluntarily move out when they stabilize. However, if they do something that endangers the well-being of other tenants then the tenant can be evicted from the residence.

With its success, there have also been some criticisms. Concerns have come up over potential funding shifts from shelter programs or other homelessness-related programs. Reduced funds can decrease the number of individuals/families served or the number of services provided. Additionally, many critics believe that beneficiaries should “earn” state support and this model doesn't require clients to take action. Lastly, there are those who believe that this model can be financially wasteful since there may be clients who won't make safer behavior changes or may return to homelessness/housing instability.

Despite criticisms, there is growing evidence around the success of the Housing First Model, not just for clients, but also within medical care and social service. One study found an average cost savings on emergency services of $31,545 per person housed in a Housing First program over the course of two years. Another study showed that a Housing First program could cost up to $23,000 less per consumer per year than a shelter program.

As communities look to implement this model, it is important that public health providers, community partners, and policy stakeholders work together to build strong relationships, increase access to coordinated care, and eliminate barriers to a better quality of life.

Public Housing

Public housing, housed in HUD, is regulated by federal, state, and local jurisdictions to provide access to low-income subsidized housing. Historically, the United States has a complicated and contentious relationship with public housing due to the bad policies and programming that unjustly targeted communities of color and those in extreme poverty. This has strongly contributed to the stigma and negative perception of living in public housing or accepting assistance. Trying to alter perception, HUD works to provide a safe and inclusive environment for their clients.

Public housing can be a great resource for many individuals and families, but can often be hard to access. Many jurisdictions have wait lists for those who qualify because housing subsidies are unavailable. Some clients are on the wait lists for years before they receive subsidies.

Shelter Programs

For homeless individuals and families, shelters are often the first intervention they will experience. Although shelters can provide many benefits, shelter culture is a challenge that can definitively deter many from accessing shelters. This is particularly true for the population we serve, who may experience discrimination, stigma, and fear while in the shelter.

It, also, important to consider the process for accessing shelters, which varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The location, the intake process, or the administrative personnel of the shelter impacts the clients willingness to seek refuge. Shelters are working to streamline and coordinate the intake process since the population served is transient, but ultimately it is up to the client to decide whether a shelter is a safe environment for their needs.

Housing Discrimination Laws

Unfortunately, housing discrimination is something that many PLWHA, LGBTQ, transgender individuals, and low-income people experience. It is important to educate, empower, and advocate for your clients, so that they are able to live comfortably. There are federal protections to eliminate discriminatory policies and practices, like the Fair Housing Act, but that doesn't stop landlords and management companies from instituting these practices.

Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act) prohibits discrimination, in any housing-related transactions, based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, and disability. Additional characteristics over time have been added as nationally recognized protected classes:

- Age

- Citizenship

- Pregnancy

- Veteran Status

- Genetic Information

States, cities, and territories may have their own added protected classes, such as*:

- Gender Identity

- Sexual Orientation

- Source of Income

- Ancestry

- Personal Appearance

- Political Affiliation

- Family Responsibilities

- Matriculation

- Status as a Victim

*Look to your own jurisdictions' policies and laws regarding housing discrimination and protected classes.