Homelessness and HIV/AIDS have a complex relationship, presenting many more challenges as providers work to improve disease outcomes for clients. Lack of housing is often an overarching barrier, with many other housing-related issues impacting stability. They can include transportation, food insecurity, job insecurity, financial literacy, housing affordability, community development, etc. These, too, must be addressed in order to help clients achieve housing stability.

When housing is provided, research shows there is a reduction in ER visits, hospitalizations, and opportunistic infections, as well as improved mental health and decreased mortality. A 2009 study, "Impact of housing on the survival of persons with AIDS," found an 80% reduction in mortality among PLWHA in San Francisco when housing support was provided. Stable housing empowers clients to better manage their health and quality of life. For example, often clients are able to adhere to medication regimes and consistently schedule and attend provider appointments, which we know can lead to viral load suppression. This benefits not only people living with HIV, but also those who are at high-risk of getting HIV.

Homeless vs. Chronic Homelessness

It is important to verify client eligibility for certain programs/services offered by HOPWA. Services are intended for low-income clients, but there are certain programs that require the person or family to be chronically homeless. Providers or case managers must have proof of chronic homelessness in order to access services.

Homeless – A person who does not have a steady, safe, acceptable nighttime residence or accommodation; is residing in a shelter; or is staying in a public/private place not designated for human occupancy (i.e., streets, cars, abandoned buildings, couch surfing, survival sex).

Chronic Homelessness – As defined by HUD, a homeless individual with a disabling condition who has been continuously homeless for at least one year or has had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years.

Housing Opportunity for Persons With AIDS

Housing Opportunity for Persons With AIDS (HOPWA), established in 1992, is the only federal funding specifically dedicated to housing and housing-related needs for low-income PLWHA. The program is housed in the Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD).

In 1988 Congress instituted the National Commission on AIDS to research the concerns and promote the policy needs from the HIV/AIDS outbreak. In 1990 the commission recommended to Congress and President George H.W. Bush the establishment of federal housing aid to address HIV-related problems, which eventually led to what we now know as HOPWA.

In FY2016, as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress appropriated $335 million for HOPWA. Since its inception, HOPWA has served approximately 52,000 households across the U.S. and Puerto Rico. During FY2015 HUD determined that 138 jurisdictions qualified for HOPWA formula allocations, including 97 Emerging Metropolitan Areas (EMA), 40 states, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

HOTMA: Housing Opportunity through Modernization

In July 2016, Congress approved HOPWA changes to modernize the formula award. Previously, HOPWA original formula was based on cumulative AIDS cases and did not account for current HIV cases. With the changes, now funding allocation will be based on:

- The number of people living with HIV (75%),

- The number of people living in poverty (12.5%), and

- Local fair market rent (12.5%)

All grantees will remain eligible and changes will be phased in over 5 years with grantee losses capped at 5% and gains at 10% of the prior year's allocation.

Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program

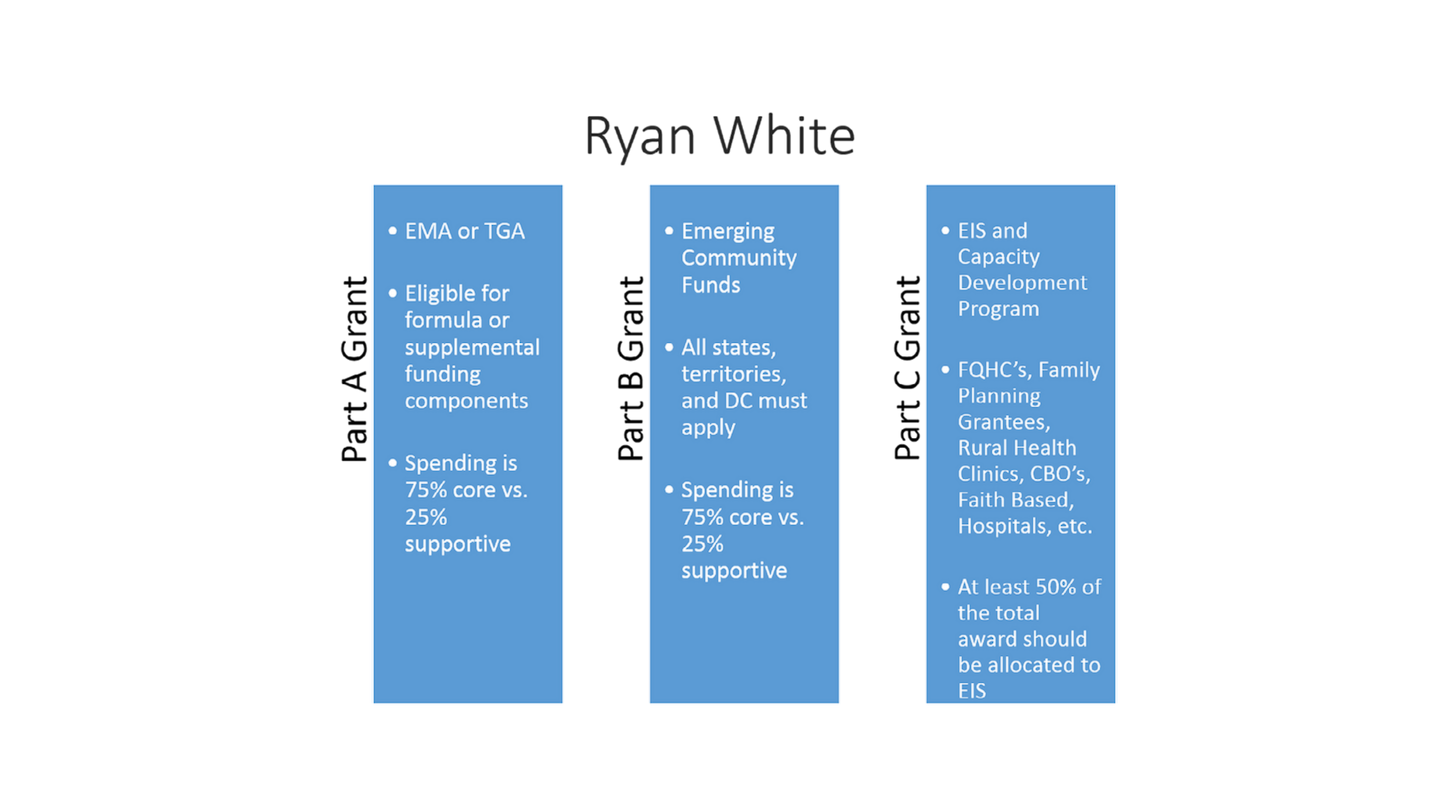

Established in 1991, the Ryan White program is the largest federally funded program for PLWHA in the U.S. It is administered by Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and HIV/AIDS Bureau (HAB). Known as the payer of last resort, funding is dispersed between 6 different parts (A-F), with Part A, B, C, and D contributing to housing services. NASTAD membership primarily focuses on Part B, which is the largest funded part & includes the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP).

EMA - Emerging Metropolitan Areas; TGA - Transitional Grant Areas; EIS - Early Intervention Services; FQHC - Federally Qualified Health Centers; CBO - Community Based Organizations

Ending the HIV Epidemic

The Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE): A Plan for America is a widespread plan with the goal to end the HIV epidemic in the United States (US) by 2030. This plan, developed and funded by multiple agencies across the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is informed by scientific research, organizational programming, and community experience and expertise.

With the intention of addressing the biggest HIV challenges in the US across four pillars (prevention, diagnose, respond, treat), this plan focuses on 57 jurisdictions that have the highest rate of HIV transmission by tailoring national tools and efforts to local needs and vision.

National HIV/AIDS Strategy

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020 (NHAS) calls upon community and governmental providers across prevention and care to address the housing needs of their communities. In order to achieve the four primary goals of reducing new infections, increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for PLWHA, reducing HIV-related health disparities and health inequities, and achieving a more coordinated national response to the epidemic, the updated strategy prioritized housing in calling for a reduction of persons in HIV medical care who are homeless to no more than five percent. Ultimately, by working to reduce homelessness providers can increase positive disease management. The strategy also acknowledges housing interventions as a main linkage component to patient-centered care.

This update marks the first time that the NHAS explicitly stated the importance of housing programs. Even still, there has been criticism of the language used to frame housing, and that it did not go far enough to assert its value. It is important that housing programs should not be viewed as only a method to link PLWH to care, but rather as evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment interventions.