Appendix 1 Disease Outbreak and Pandemic Response Planning

In addition to natural and man-made disasters, health departments also play a critical role in responding to disease outbreaks and pandemics. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides guidance and support to jurisdictions during such events. Examples include state and local government planning resources in the event of disease outbreaks.

ADAPs have an important role in supporting continued access to HIV treatment and other essential medications where disease outbreaks and pandemics – and public health responses to outbreaks and pandemics – can disrupt typical administrative functions of the program and access to pharmacy services. ADAP structures typically include large networks of pharmacies or medication distribution points strategically located across the jurisdictions they serve. These network infrastructures can provide efficient methods for distributing medications to large segments of the population, or to targeted areas impacted by a particular outbreak.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, NASTAD created a website dedicated to the pandemic and released several resources to “help ensure the continuity of essential programming and the protection of people living with and vulnerable to HIV infection and viral hepatitis.”

COVID-19 Considerations

Impact on ADAP Administrative Structures, Operations, and Capacity

The COVID-19 pandemic affected daily operations for many ADAPs, and several programs implemented policies and procedures to protect client health and limit disease spread. Changes included:

- Reorganizing programs due to reassignment of staff critical to emergency response operations, surveillance, and contact tracing;

- Implementing simplified application process and procedures, including temporary acceptance of e-signatures in lieu of “wet” signatures;

- Creating emergency recertification processes;

- Discontinuing program disenrollment protocols;

- Reducing requirements around laboratory reporting criteria (e.g., waiving current CD4 and viral load status);

- Reassessing income documentation policies (e.g., non-inclusion of COVID-19 economic stimulus payments and additional unemployment stimulus payments in Federal Poverty Level calculations for program eligibility); and

- Implementing 90-day medication fills and mail/courier delivery of medications.

State Examples of operations and policy changes implemented during COVID-19 pandemic:

Louisiana: Lifted all prescription fill restrictions for the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. ADAP reached out by phone instead of via fax/mail. Relaxed policies around documentation submission when/if clients could not access certain documents (ex., Medicaid/Social Security determinations, etc.)

North Carolina (NC HMAP): To fully coordinate with providers that were providing telehealth appointments with HMAP clients, HMAP received support from HRSA to allow client and clinician verbal consent on HMAP applications in lieu of written signatures. Staff permitted to work remotely were issued laptops and had established VPN to connect directly to the secure NC DHHS server. The office staggered in-office and remote work while practicing social distancing and wearing masks.

Return to Office Consideration

The process for determining when ADAP staff will return to the office will vary from state to state and may include assessing staff readiness to return to the office, limited or staggered building access for essential personal, and other considerations. Please visit CDC Workplace, School and Home Guidance and HHS COVID-19 Workforce Virtual Toolkit for additional information

Data Privacy Considerations in a Working-from-Home Environment

It is critical for ADAPs to have mechanisms in place to maintain data privacy when handling protected health information working offsite.

The HHS COVID-19 Workforce Virtual Toolkit provides a multitude of COVID-19-related resources, templates, and resources for public health professionals. Each jurisdiction should work with their health department human resources management team to obtain current virtual telework agreements, confidentiality statements, and information around secure file transfer protocols.

Questions for consideration:

- Is your eligibility/delivery system virtual or are you still using paper/fax machines?

- Can HIPAA be maintained away from office setting?

- Do staff have laptops and an established VPN to connect directly to your secure server?

Medication Access Considerations

Prescription drug supply and distribution chains essential to ADAP client medication access depend on a number of key entities (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient [API] producers, manufacturers, wholesalers, and pharmacies) that can be affected by disasters and other hazards, including pandemics. These entities – or the movement of products between the entities – are also subject to their own emergency preparedness plans or COOPs, which can affect access to antiretrovirals and other important medications.

In early 2020, many ADAPs moved to allow early refills and/or 60- or 90-day fills for full-pay medication program clients, in support of stay-at-home recommendations and heightened safety precautions surrounding potential COVID-19 morbidity and mortality risks among people with HIV. Many insurance programs, including Medicaid and commercial insurance carriers, also implemented prescription fill/refill flexibilities in support of quarantine and social distancing recommendations.

There were concurrent concerns regarding medications shortages due to the potential impact of COVID-19 infection and stay-at-home recommendations on drug manufacturing, as well as sharp increases in demand for prescription drugs required to treat COVID-19. Additionally, many wholesalers implemented “fair share” allocation processes to manage prescription drug inventories. To ensure that all pharmacies and direct purchasers, including ADAPs, received their usual allocations to meet their average monthly dispenses, wholesalers limited fulfillment of additional orders and many pharmacies experienced challenges meeting early refill and 60- or 90-day fill demands.

Individual pharmacies within an ADAP’s network can also be affected by disasters and other hazards, which requires ADAPs to be prepared for client medication access challenges at the local level.

Questions for consideration:

- In the absence of existing early refill and/or 60- or 90-day medication fill/refill allowances, does your program have contingency policies or plans to allow these?

- Is your pharmacy network sufficient to meet the needs of clients in the event of local disasters or other hazards that can disrupt access to essential medications?

- Can your contract pharmacy(ies) operate from alternative locations if compromised?

- Has your (or your pharmacies’) wholesaler(s) implemented “fair share” allocation procedures in response to spikes in demand?

- Can your contract pharmacy/pharmacies provide shipping or courier delivery of medications?

- In the event of statewide emergencies or disasters, can you coordinate with ADAPs in surrounding states to provide information, streamline program eligibility verifications or provide emergency medication access to evacuees?

Rural Considerations and Impact of Resources

Ensuring there are mechanisms in place to sustain continuity of services for clients in rural areas is critical. These services include telehealth, remote pharmacy access, and implementation of electronic communication methods (email or text message), if clients do not have access to a computer or email.

The following resources can help jurisdictions explore or expand the current telehealth plan workflow and prepare clients for virtual appointments. These include webinar recordings and toolkits for healthcare workers as well as rural, Spanish speaking, faith-based, older adult, and racial and ethnic minority communities

Appendix 2 Federal and State Shutdowns

Occasionally, a lack of approval on the federal budget for an upcoming fiscal year may result in a “government shutdown,” when nonessential offices of the government cease operations. The federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is responsible for ensuring that agency contingency plans are in place in the event of a government shutdown. The OMB maintains a contingency plan describing how operations will proceed for each federally funded agency.

State and local governments may experience similar shutdowns if budgets are not approved, with contingency plans guided by state and local laws and policies. ADAPs should be familiar with how federal, state, and local shutdowns can affect program funding, and should include planned responses in the COOP.

Appendix 3 Cybersecurity Preparedness

According to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), cybersecurity is the art of protecting networks, devices, and data from unauthorized access or criminal use and the practice of ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. This section provides general guidance around data security and data privacy topics and perspectives from ADAPs. However, each jurisdiction should work with their health department IT team to ensure your agency is well protected from cyberattacks.

Definitions:

Data security: Data security protects digital information from unauthorized access, corruption, external attackers, and malicious insiders.

Data privacy: Data privacy governs how data is collected, shared, and used.

Social engineering: According to USA Kaspersky, social engineering is a technique used to gain private information, access, or valuables. In cybercrime, these “human hacking” scams lure unsuspecting users into exposing data, spreading malware infections, or giving access to restricted systems. Common methods used by social engineering attackers include phishing attacks.

Phishing: Phishing attackers pretend to be a trusted institution or individual in an attempt to persuade you to expose personal data and other valuables. Attacks using phishing are targeted in one of two ways:

1. Spam phishing - is a widespread attack aimed at many users.

2. Spear phishing - uses personalized information to target particular users.

There are numerous examples of social engineering techniques, and it is strongly encouraged to work with your health department IT team to ensure that your agency is well protected from phishing attacks.

Ransomware: According to CISA, ransomware is an ever-evolving form of malware designed to encrypt files on a device, rendering any files and the systems that rely on them unusable. Malicious actors then demand ransom in exchange for decryption. For more information about this growing cyberthreat, please visit the Joint Ransomware Guide, which includes best practices and a response checklist (Page 11) that can serve as a ransomware- specific addendum to an organization's cyber incident response plans.

State Example

In November 2019, several state offices in a jurisdiction, including the state health department, experienced a ransomware attack. The impact to ADAP included a complete loss of phone, email, fax, internal network drives, and internet capabilities for two to three days plus intermittent access to these services over the next two to three weeks.

Cybersecurity Preparedness Considerations and Questions to Ask

NASTAD recognizes the crucial need to highlight technological vulnerabilities to health departments and the impact on daily operations and clients’ personal health information if there is a cyberattack. We encourage ADAPs to work with your State IT department to help ensure any cybersecurity breaches or attacks are minimized.

Recommendation and considerations from ADAPs polled regarding their cybersecrity concerns.

- Is the existing system in place secure enough to protect against a hack, ransomware?

- Can staff access the Agency’s virtual private network (VPN) easily?

- Do you have enough equipment (laptops, MiFi’s, etc.) for all staff?

- Would you consider moving all client data to secure jProg sponsored cloud versus on local server(s) using an MOU and Business Associate Agreement (BAA)? Examples include computer suite software or cloud web services. Please keep in mind with cloud software, the contingency is more reliant on the cloud software service levels. This tends to minimize contingency plans as follows:

- Essential Mission and Business Functions - List of agency critical functions

- Recovery Objectives for all IT applications - Falls under three different categories:

- Maximum Tolerable Downtime (MTD) is the time after which the process being unavailable creates irreversible consequences.

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO) is a metric that helps to calculate how quickly IT recovers applications and infrastructure services following an emergency in order to maintain business continuity.

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO) is a measurement of the maximum tolerable amount of data to lose. RPO is helpful in determining how often to perform data back-ups.

Appendix 4 Creating and Maintaining a COOP Checklist for ADAPs

- Identify, establish, and maintain regularly (e.g., annually) a core ADAP Emergency Preparedness Committee comprised of four critical personnel with significant knowledge of ADAP administrative operations and at least one member with an in-depth knowledge of the state preparedness plan.

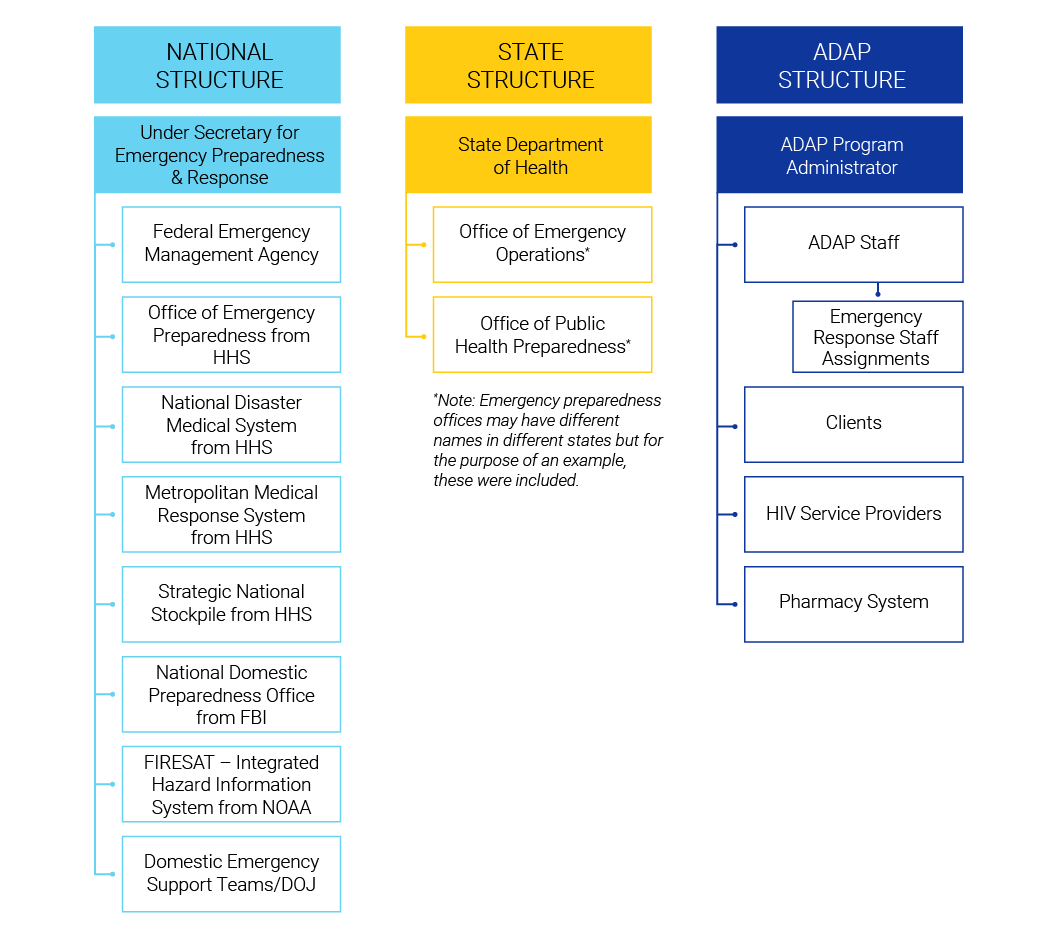

- Obtain and review the state health emergency response plan for its structure and chain of command. Develop and maintain an ADAP-specific chain of command incident management reporting structure.

- Define the essential functions necessary for ADAP to continue providing antiretroviral medications and ADAP services during an emergency.

- Create personnel roster of key staff as well as backup personnel. Create a key personnel contact list.

- Create a list of equipment and resources that are essential for personnel to function.

- Review a hazard vulnerability analysis of your state specific ADAP and distribution locations and prioritize the most likely threats. Create an emergency preparedness “to go” bag that includes critically necessary equipment.

- Identify and draft policies regarding medication distribution strategies. These may include using established point of distribution sites.

- Review the emergency planning guide with the state health department’s emergency planning division. Consider drills and exercises in conjunction with the overall state health department to test the plan and make improvements to the plan if needed.

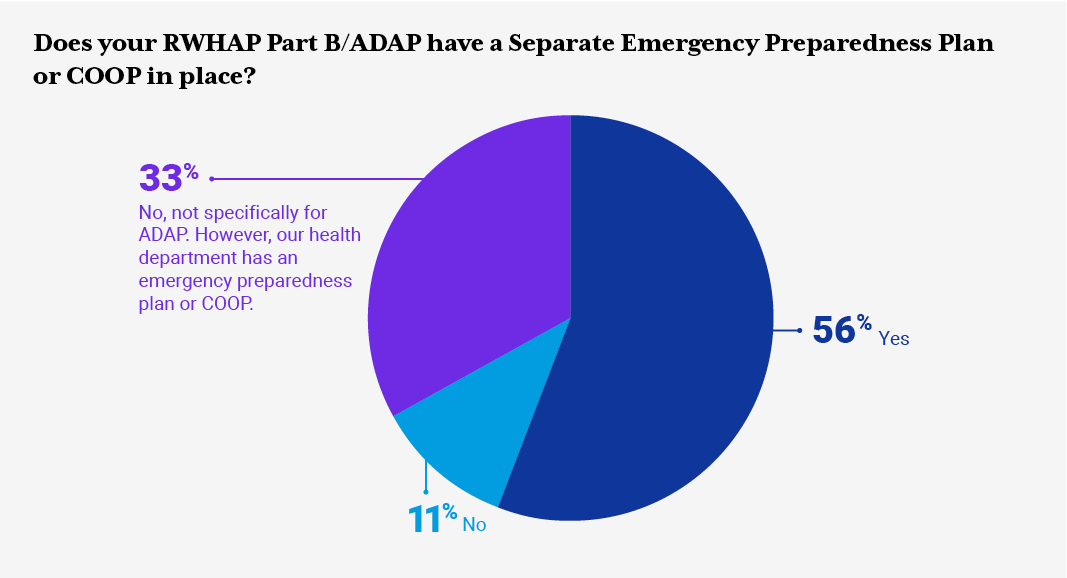

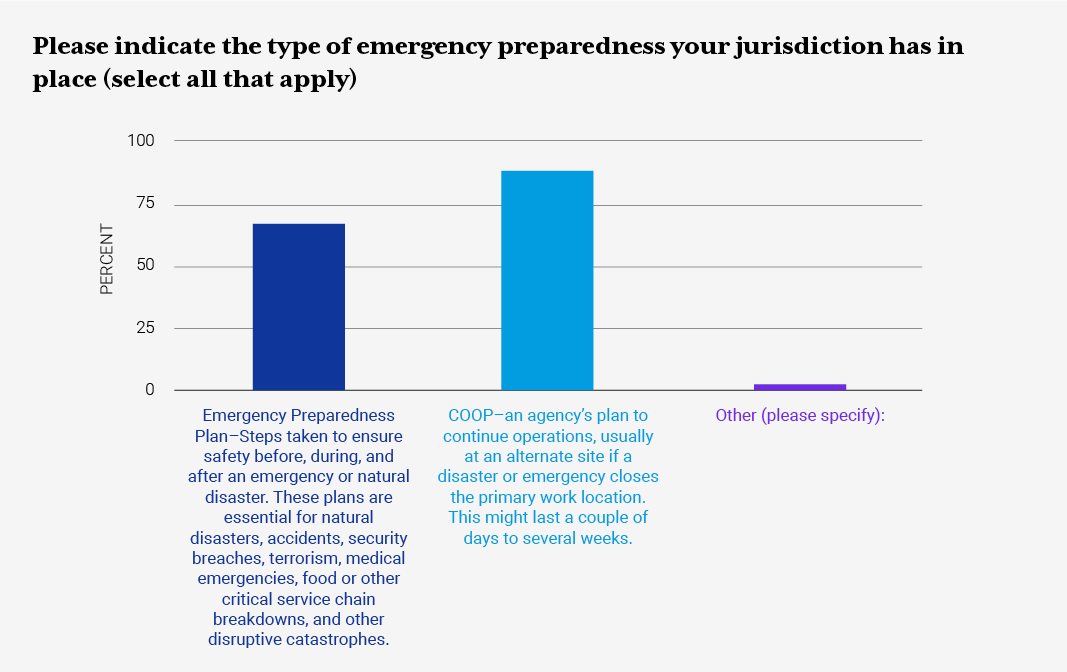

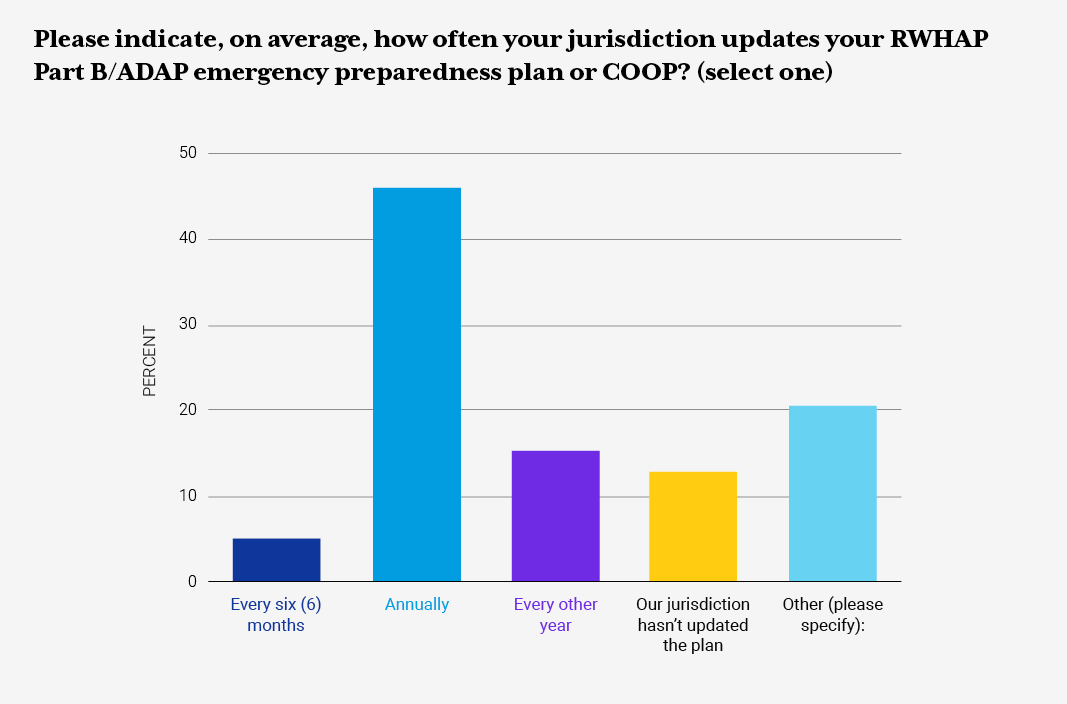

Appendix 5 RWHAP ADAP Emergency Preparedness Request for Information Results

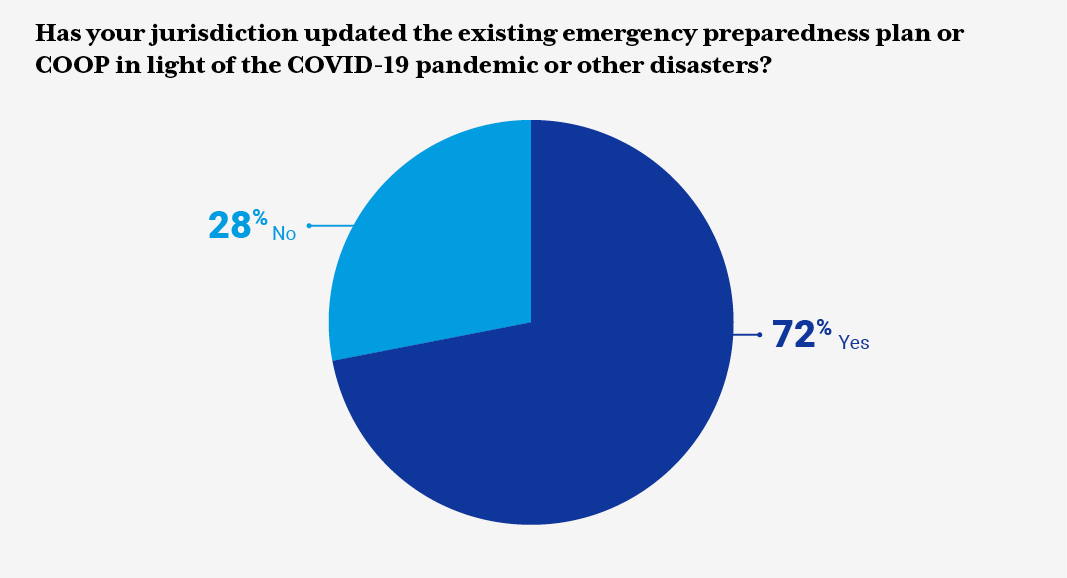

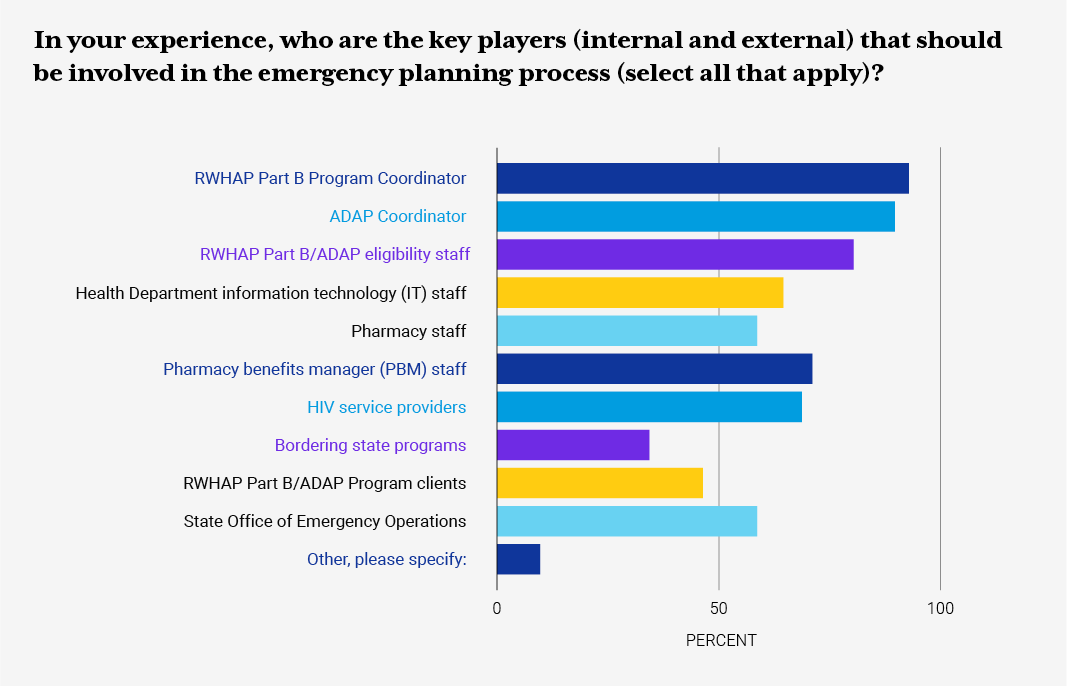

In April 2021, NASTAD conducted a Request for Information (RFI) to update existing emergency preparedness guidance, templates, and resources to share with state and territorial RWHAP ADAPs. NASTAD anticipates these findings will be useful to jurisdictions considering developing or updating existing emergency preparedness resources. NASTAD expresses sincere gratitude for jurisdictions that took the time to complete the RFI and shared additional resources.

RWHAP/ADAP Part B health department staff were asked to provide information around the type of emergency preparedness plan(s) their jurisdictions have in place, focus areas the plan addresses, and frequency of updates to the emergency preparedness plan or COOP. The RFI also inquired about RWHAP Part B/ADAP-related policies and protocols around COVID-19, ADAP eligibility and recertification, client communication letters, medication access policies, and other resources. Additionally, the RFI inquired about jurisdiction pandemic planning, stay-at-home orders, and the impact on ADAP daily operations.

Please see the summary of findings and lessons learned below.

Lessons Learned:

-

“There are a lot of things that come up that are unexpected, and you have to be as flexible as possible while following regulations.”

-

“Be flexible. Things haven’t always turned out the way we planned them, so we had to revise in the moment and take note of those revisions in our plan.”

-

“Establish a regular schedule to update it and constantly improve it; it is a living document. Prepare a summarized excel spreadsheet version for ease of review and assignments, always prepare a Go-Folder with everything you need and be specific about who should take it with them. Utilize docking stations for computers so they may be used away from the office seamlessly. Have clear call-forwarding instructions and have them worked into your plan.”

-

“Our state agency has a procedure for creating and updating these types of plans. The state agency process is helpful but not as detailed as would be most helpful for ADAP continuity planning. Programs should work to expand on agency-wide processes to have the level of detail most helpful for ADAP.”

-

“Be flexible and willing to adjust the policy. You will not be able to predict everything.

NASTAD Emergency Preparedness Planning Webinar (2020)

In 2020, NASTAD held a webinar titled, Planning for 2020…and Beyond: Emergency Response Planning for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program AIDS Drug Assistance Programs. The webinar featured staff from North Carolina, Louisiana, and Houston health departments.

NASTAD wanted to ensure that lessons learned and considerations shared during the webinar were also included in this guide since much of the information gained from the webinar is as valuable today as it was in early 2020 and before the COVID-19 pandemic.

NASTAD extends gratitude to state partners featured on the webinar and anticipates that this information will be beneficial to health department staff in the development or revision of their current emergency preparedness planning resources and tools. The recording of this webinar is included in the resource section.

Webinar Tips and Lessons Learned

- Ask for help and frequently communicate with CDC and HRSA project officers.

- Do your planning during off-peak/down time and don’t be afraid to be the squeaky wheel of accountability.

- Establish networks (including working with neighboring states) ahead of time to build solid partnerships and clarify roles.

- Conduct a trial run or drill with staff to see what went well and identify areas of improvement.

- Research external laws and policies that might inhibit an effective emergency response (such as state medical licensure requirements & remote work policies).

- Share information relevant on provider operational status to planning groups.

- Every single jurisdiction is vulnerable.